Back when I was a kid, we called Chanukah the Festival of Light, in commemoration of the eight days that the candelabra (hanukkiya) in the Temple burned on one day’s supply of oil.

As I got older, however, I began to think of it more as the Festival of Frying, since oil plays such a central role in the holiday. We eat latkes (potato pancakes), fried chicken and/or fish, french fries (a non-traditional favorite), and anything else one can imagine that’s both kosher and deep-fried.

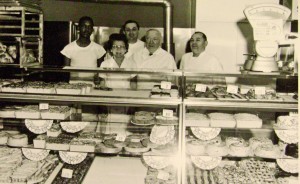

Jelly doughnuts (sufganiyot in Hebrew), were never part of my grandparents’ Chanukah traditions (we ate latkes), but for many Jews are an integral part of the holiday. So herewith, Norm Berg’s recipe for sufganiyot, straight out of Inside the Jewish Bakery .

Makes: about three dozen

|

Volume |

Ingredient |

Ounces |

Grams |

Baker’s Percentage |

| ½ cup | Shortening |

3.50 |

100 |

11% |

| 2/3 cup | Granulated sugar |

4.75 |

130 |

14% |

| 2¾ tsp | Table salt |

0.625 |

16 |

2% |

| ½ cup | Nonfat dry milk (optional) |

2.25 |

65 |

7% |

| 2 | Large eggs, beaten |

3.50 |

100 |

11% |

| 2¼ cups | Water |

19.00 |

540 |

58% |

| 1¼ tsp | Vanilla extract |

0.625 |

16 |

2% |

| Zest of 1 lemon |

0.25 |

8 |

1% |

|

| 6 2/3 cups | Bread flour, unsifted |

32.75 |

925 |

100% |

| 2 tbs + 2¼ tsp | Instant yeast |

1.25 |

35 |

4% |

- Put the shortening, sugar, salt and dry milk into a mixing bowl and blend until smooth, about 8-10 minutes, if by hand and about 4-5 minutes using the flat (paddle) beater at medium (KA 4) speed if by machine.

- Beat the egg lightly and incorporate into the shortening mixture and continue blending until smooth, 2-3 minutes, then add the water and flavorings, mixing to form a slurry.

- Reduce the speed to low (KA 2) and slowly incorporate the flours and instant yeast, forming a smooth dough.

- Switch to the dough hook and knead for another 8-10 minutes, until the dough forms a ball around the hook and pulls away from the sides of the bowl.

- Knead the dough on a lightly floured board until it’s no longer sticky, then form it into a ball, place in a lightly oiled bowl, cover with plastic and ferment until doubled, about 45 minutes.

- Turn the dough out onto a moderately floured board, flour the top surface lightly but evenly to prevent sticking and punch down. scale the dough to 1.0-2.0oz/30-55g pieces, roll into balls and flatten to ¼”-3/8”/0.6-1.0cm thick.

- Preheat your frying oil to 350°-375°F/175°-190°C.

- Place the dough pieces on a frying screen (I use 10″ pizza screens, available at kitchen supply vendors). Proof until slightly less than doubled in size and a finger gently pressed into the dough leaves an indentation that doesn’t spring back, 45 – 60 minutes. Be very careful when you handle the doughnuts, as too much touching will result in a collapsed product. Don’t under any circumstances transfer the doughnuts to the oil by hand.

- Lower the frying screen with the doughnuts into the oil and fry until golden brown on the bottom. Turn the doughnuts using the handle of a wooden spoon or a pair of bamboo chopsticks and fry for another minute.

- Lift the frying screen and the doughnuts out of the oil, let any excess oil run off and transfer to paper towels to drain. When they’re cool, use a pastry bag and plain tip to inject them with jelly, custard, pudding or other smooth filling. Finish the with honey glaze, simple icing or powdered sugar.