Not too long ago, during a radio interview centered on “Inside the Jewish Bakery,” the host asked me, “What is a Jewish bakery?” I have to confess, I was stunned: no one had ever asked me that question, nor, indeed, had I ever asked it of myself. In my world, everyone knows what a Jewish bakery is – a bakery that sells Jewish baked goods.

But here’s where it gets complicated. What exactly are “Jewish baked goods?” The ones that come first to mind – bagels, rugelach, onion rolls, challah – appear to be no-brainers, but in fact all can be traced back through their Yiddish forebears to the gentile Central and Eastern European societies in which the Jews found themselves living at various times.

But here’s where it gets complicated. What exactly are “Jewish baked goods?” The ones that come first to mind – bagels, rugelach, onion rolls, challah – appear to be no-brainers, but in fact all can be traced back through their Yiddish forebears to the gentile Central and Eastern European societies in which the Jews found themselves living at various times.

Take bagels, for instance. In America, we think of them as a Jewish food that made good, rising to the pinnacle of the American mainstream and assimilating away their “Jewishness”. But boiled/baked ring breads made of double-helix dough strands, called obwarzanki are the signature street food of Kraków, Poland, and have been for centuries. And lest anyone argue that “Jewish” bagels don’t feature that ropelike twist, I would point out that a 1936 photo in the collection of the New York Public Library shows a Jewish New York City bagel peddler selling what clearly are twisted obwarzanki. At the same time, a 1938 photo in the YIVO collection shows a bagel seller in Lithuania selling the untwisted bagels we’re all familiar with. Go figure.

So how about challah? Nothing more Jewish than that, right? Well, although the term “challah” is derived from the Torah, the bread itself was a loan from 14th and 15th century German Christians, who honored their Sabbath with braided loaves, according to Jewish foodways historian John Cooper. On top of that (and on top of the loaves), the custom of decorating breads with symbols of faith such as birds, hands, keys and ladders – also often thought of as uniquely Jewish – also can be traced back to the Christians of Central Europe. Even the term “koyletch,” an alternative name for challah throughout Yiddish Europe, is of Slavic origin. And to bring things full circle, a braided, egg-glazed sweet bread called chałka is a staple offering in the bakeries of today’s Poland.

The same is true of knishes, babkas, rolls (bulkes), rye breads – you name it and the gentile host cultures had it before the Jews. Even most modern favorites come from someplace else, most obviously rainbow cookies, whose horizontal layers of red, yellow and green reprise the Italian flag and trumpet their origin.

The same is true of knishes, babkas, rolls (bulkes), rye breads – you name it and the gentile host cultures had it before the Jews. Even most modern favorites come from someplace else, most obviously rainbow cookies, whose horizontal layers of red, yellow and green reprise the Italian flag and trumpet their origin.

So if everything in the Jewish bakery came from someplace else, what, after all is a “Jewish bakery?”

In my view, nothing less than the history of a people’s wanderings from place to place – from Eretz Yisrael to the Roman Empire, from Rome northward into the Rhine Valley, then west into France and England and east into Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, Lithuania, Poland and Russia. At every stop, the Jews found the foods of their gentile neighbors and adapted them to the laws of Kashrus. And when it came time to move again, they took those foods with them and added to their repertoire the foods of their next home, again adapted to Kashrus.

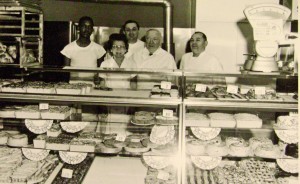

And so the Jewish bakery is really a time capsule, a distillation of a thousand years of Diaspora, come to rest in a row of glass-fronted display cases and shelves full of bread and rolls behind the counter. Every bread and roll, every pastry, cake and cookie, reflects a specific time and place in our communal history and connects us tangibly (and edibly) to our shared experience. And you thought it was only a bakery!

Today, the world’s food culture is rapidly homogenizing. You can find U.S. fast-food franchises in Tokyo, Beijing and Moscow; Japanese ramen-chain outlets in New York, Los Angeles and London. And bagels are everywhere. TV food porn, as my daughter likes to call it, has universalized once-obscure ingredients and globalized technique and plating to the point where cooking has morphed from the deepest, most visceral (pun intended) expression of a culture rooted in time and place to a media-driven vehicle for individual creativity.

And while I do ap preciate the pure sensual pleasures of sculpturally composed, artfully conceived and executed coups de table, I’m also very much aware that even the best of them lack the authentic Yiddish tam of my grandmother’s kroyt borscht, a long-simmeredsoup – a stew, really – made from beef flanken and an abundance of winter vegetables – cabbage, beets, turnips, carrots, potatoes and onions.

preciate the pure sensual pleasures of sculpturally composed, artfully conceived and executed coups de table, I’m also very much aware that even the best of them lack the authentic Yiddish tam of my grandmother’s kroyt borscht, a long-simmeredsoup – a stew, really – made from beef flanken and an abundance of winter vegetables – cabbage, beets, turnips, carrots, potatoes and onions.

Meanwhile, at the other end of the spectrum, the mass-market processed food industry is wreaking its own Holocaust on family-run, made-from-scratch restaurants and bakeries, and in the process, severing the connection between people and their personal and communal histories. And sadly, as those restaurants and bakeries die, so too, dies a piece of our cultural history that most of us barely recognize, let alone miss, until it’s gone.

_______________________

Photos courtesy of Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, Tamiment Library, New York University